What links Catherine O’Hara, Enrique Iglesias, Donny Osmond, and me? At face value, at least, not a lot. Look beneath the skin, however, and you would see a striking similarity: our hearts beat on the right, not the left. In fact it goes beyond mere dextrocardia, which would mean only the heart is transposed; instead, all our organs are placed in mirror image to the norm. We are linked by abnormality: we all have situs inversus.

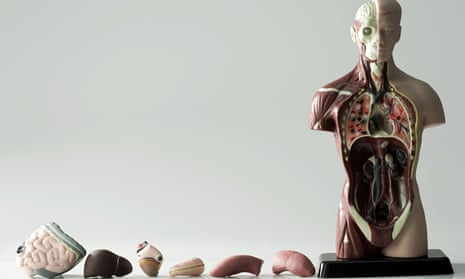

Situs inversus is a rare congenital condition in which all of an individual’s internal organs in the thorax and abdomen are positioned on the opposite side to where they should be. The liver, for instance, is now on the left, the spleen on the right. Flipped, for want of a better word.

In some cases a person can live most of their life without realising they have situs inversus. Indeed, it has been reported that Donny Osmond was only aware of his condition after his case of appendicitis was overlooked because his appendix wasn’t where the doctor expected it to be. As such, and with an estimated occurrence of one in every 10,000 births, situs inversus totalis - the full term for complete anatomical reversal - has intrigued scientists for centuries. Many believe the condition holds clues to understanding how our bodies differentiate right from left, and the significance behind such a preference.

I was diagnosed with situs inversus totalis at six months old. Often, recorded signs of a reversed anatomy are dismissed as an error of the x-ray technician, the left and right labels supposedly mixed-up. It was only when I was taken to hospital with unrelated breathing problems that doctors began to consider the possibility that I had situs inversus. “Sit down and listen to everything I tell you”, the doctor told my parents, who, even after listening intently, were left in a state of disbelief. Several medical staff hurried into the room, excited. Medics may only come across one case of situs inversus in their careers, and I was later invited to take part in a Guess What’s Wrong With The Baby trainee doctor event.

For the last twelve years I have worn a MedicAlert bracelet on my left wrist to notify people of my rare condition. Turn it over and emergency medical staff are informed that I have “Complete Situs Inversus Normal Ciliary”. Rather than being simply an accessory or conversation piece, it serves the valuable purpose of preventing the somewhat unfortunate-sounding possibility of having an operation on the wrong side in an emergency.

Since all my organs have assumed the exact opposite location, situs inversus does not affect my overall health. I was very lucky; had only a few of my organs moved, or had they grown in random positions - as is the case with situs ambiguus - the condition would have been very serious. Of those born with situs inversus, 25% have Kartagener Syndrome (also referred to as primary ciliary dyskinesia), a defect in the cilia that line important organs and tracts, such as the respiratory tract, causing bronchitis, and reducing male fertility.

In other circumstances, the failure of one of the organs to move to the other side can further complicate the individual’s health, by causing entanglement. This often proves fatal.

There is also a strong probability that people born with situs inversus have heart problems. Speaking with adult congenital cardiologist Dr Dan Halpern at New York University’s Langone Medical Centre in July, I began to fully understand the condition’s implications. “You are the rarity,” he said, before delving into an animated description of the cardiovascular impact a reversed anatomy can have.

The most common heart problem, Halpern told me, is the transposition of the great arteries: instead of the great vessels arising from the heart criss-crossing over each other as they should, they lie in parallel. Alongside this, the main ventricles of the heart are inverted, or the great vessels arise from the wrong chamber. In the event of heart surgery, situs inversus can involve complications, since organs such as the heart are chiral - ie. they can be distinguished from their mirror image. Just think what would happen if you tried, for example, to attach a left hand to a right wrist. A similar geometric problem occurs if a donated heart from a non-situs inversus donor is transplanted into someone with situs inversus. The donor’s heart must be placed into the reversed position, and the surgeon needs to consider aspects such as the different weighting and the need to ensure the reattachment of the asymmetric blood vessels. It is almost like trying to complete a jigsaw puzzle with the wrong pieces.Thankfully, twenty years on from my surprise diagnosis I have been able to lead a perfectly normal life - albeit one with a growing curiosity for what situs inversus entails; the history of its discovery, its wider cultural implications and why it occurs.

Although Aristotle cited two cases of transposed organs in animals, situs inversus was first discovered in Naples by the anatomist and surgeon Marco Severino, in 1643. A century later the Scottish physician Matthew Baillie recorded the reversal as situs inversus, from the Latin situs, as in “location”, and inversus for “opposite”. Situs solitus is the normal structure, while isolated levocardia refers to when the heart alone remains on the left - an even rarer condition.

Baillie’s 1788 account of the discovery during a seminar at the Hunterian School of Medicine conveys the shock the room of young doctors felt as they were faced with the mirror image. His text explains that from the outside the deceased man appeared to be of normal disposition, but that “upon opening the cavity of the thorax and abdomen, the different situation of the viscera was so striking as immediately to excite the attention of the pupils”. While the right lung is usually divided into three lobes, the pupils discovered “‘exactly contrary to what is found in ordinary cases”. He goes on to explain that “the apex of the heart was found to point to the right-side nearly opposite to the sixth rib, and its cavities as well as large vessels were completely transposed.”

The account also tells of the “considerable pains” Baillie took to establish how the condition had affected the man while he was alive. In researching the life of the deceased it was established that “the person, while alive, was not conscious of any uncommon situation of his heart.” It seems probable that if such a finding had been made in medieval times, a person with situs inversus would most certainly have been branded a witch or demon posthumously.

Artists and writers have explored the implications of situs inversus. Understandably so: it makes for a cracking plot twist. The titular character in Ian Fleming’s 1958 James Bond novel Dr No is saved from a bullet because of his dextrocardia. In Her Fearful Symmetry, Audrey Niffenegger introduces situs inversus during the postmortem of a twin. During the period 1452-1519, Leonardo Da Vinci is alleged to have been one of the first to depict the situs inversus anatomy - but then again, he did write back to front.

We consciously seek to attribute symbolism to structures that are formed in nature, investing our belief in the left-right asymmetry norm. Most notably, the heart and its position has always held an important cultural significance. America’s pledge of allegiance relies on the belief that the heart veers to the left of the thorax. In the Middle East, placing a hand over one’s heart after shaking hands with someone conveys respect, but also forges trust. The playground promise “cross my heart and hope to die”, started life as a religious oath, Christian in origin. “Hand on heart” suggests a sense of truth. Are these pledges and customs compromised if the right hand covers flesh and nothing more?

Of course, bodies come in many forms. Beneath the skin the illusion of regularity can be overturned, the body’s complexity brought to the light.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion